Policy making

«The Effects of Good Government on City and Country» by Ambrogio Lorenzetti from 1338 shows a specific moment in urban history - where city and country co-existed in relative harmony. (1) It also refers to the reciprocal relationship between city and country, one cannot exist without the other as the land produces food that the city needs. Therefore one cannot make rules and decisions without considering the other. Acknowledging the importance of cities for the global population food and nutrition that were managed on national or global levels, shifted to city politics. Cities were given more responsibility to care for their nutrition and how they manage their surroundings and accordingly their resources.

In 2015 Zurich signed the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact. The pact was launched at the Expo «Feeding the Planet, Energy for life» in Milan under the initiative of the mayor at the time, Giuliano Pisapia. The aim was to achieve a more sustainable, fairer and healthier food production. (2)

«The Milan Urban Food Policy Pact is an international agreement of Mayors. It is more than a declaration, it is a concrete working tool for cities. It is composed by a preamble and a Framework for Action listing 37 recommended actions, clustered in 6 categories. For each recommended action there are specific indicators to monitor progresses in implementing the Pact.» (3) The pact claimed that cities are home to over half of the world’s population and therefore have a strong strategic meaning for developing sustainable food systems and promoting healthy diets. Even though cities differ to each other, «they are all centres of economic, political and cultural innovation, and manage vast public resources, infrastructure, investments and expertise.» The importance of food is now being acknowledged by the UN - they are holding a UN Summit on Food Systems this summer in Italy and cultural institutions like the Instituto Svizzero are taking part in the conversation through their series «bites of transfoodmation».(4) These summits are concerned with resilient food chains that lead to «planetary well-being, (gender) empowerment and interconnectedness of the new system, livelyhood and wellfare of people.» (5) They also ask the question, how we could «build new societies through the lens of food.»(6)

In Zurich, the municipal ordinance article on the promotion of sustainable nutrition was approved 2017 by Zurich’s inhabitants. Based on this, the «Sustainable Nutrition Strategy» was adopted in 2019, now working under the head of department Yvonne Lötscher.(7) The policies are clear and rather comprehensive, but a spatial formulation seems to be missing.

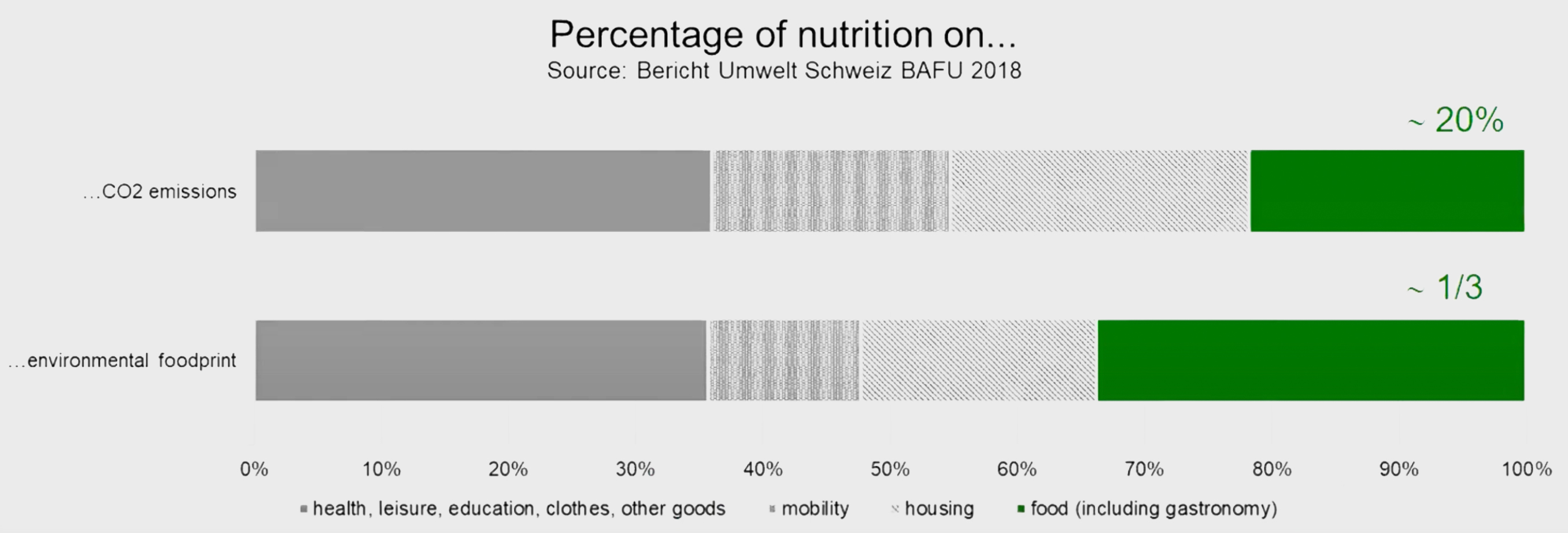

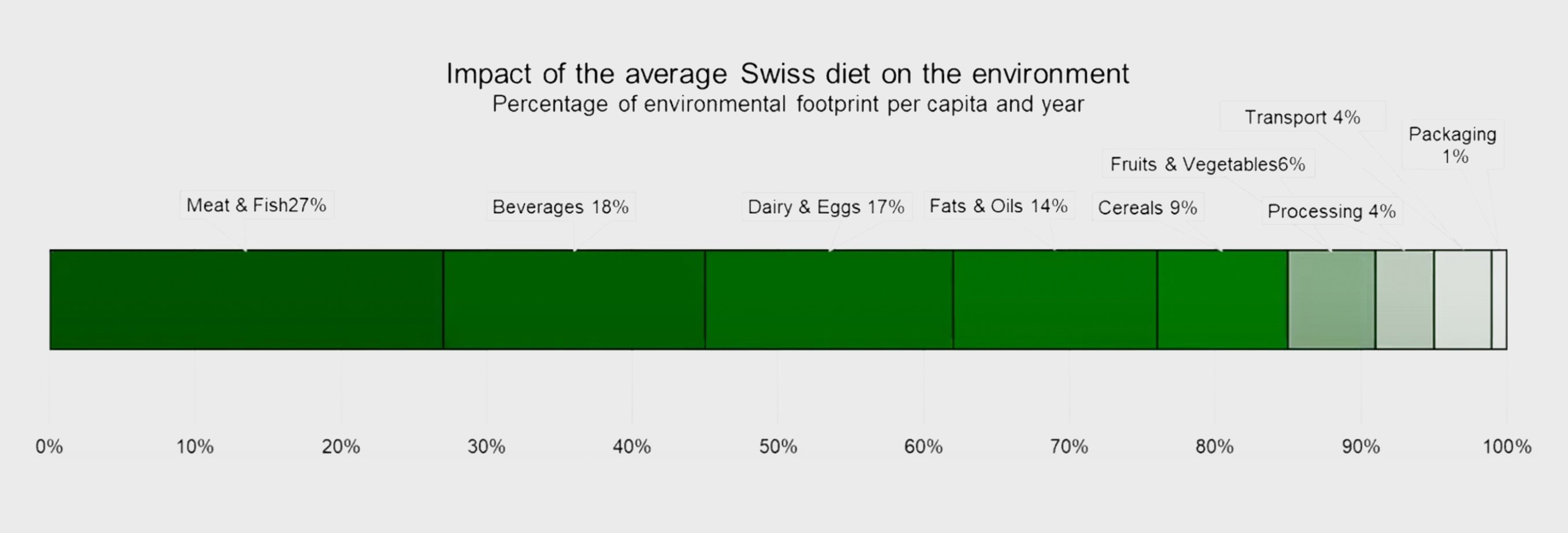

The strategy is part of the 2000-Watt strategy of which Zurich is planning to achieve major steps by 2050. (8) This is acknowledging food’s impact on the environment and therefore also sustainability. Food is generating 20% of the CO-2 emissions of a Swiss citizen and makes up 1/3 of the environmental footprint leading to biodiversity loss, emissions, eco toxicity, land use problems based on consumption. Especially 4 groups of foods are responsible for emissions: to 27% meat and fish, 18% beverages like coffee and alcohol, to 17% diary and eggs and to 14% fats and oils. Fruit and veggies only have an impact of 6%, meaning they are not only good for a healthy diet but also for the environment. In comparison to this transport only amounts to 4%. These emissions occur because diets also seem to be out of balance, people tend to eat to sweet and salty and too many fats and proteins. The strategy also mentions potential benefits of a plant based diet. In Zurich’s definition sustainable food takes into account environmental, health, economic and social justice considerations, stating that a healthy nutrition should be available to everyone. The strategy of the city consists of 5 fields of action:

1) Information and education: Schools, Administrative Knowledge, Dialogue

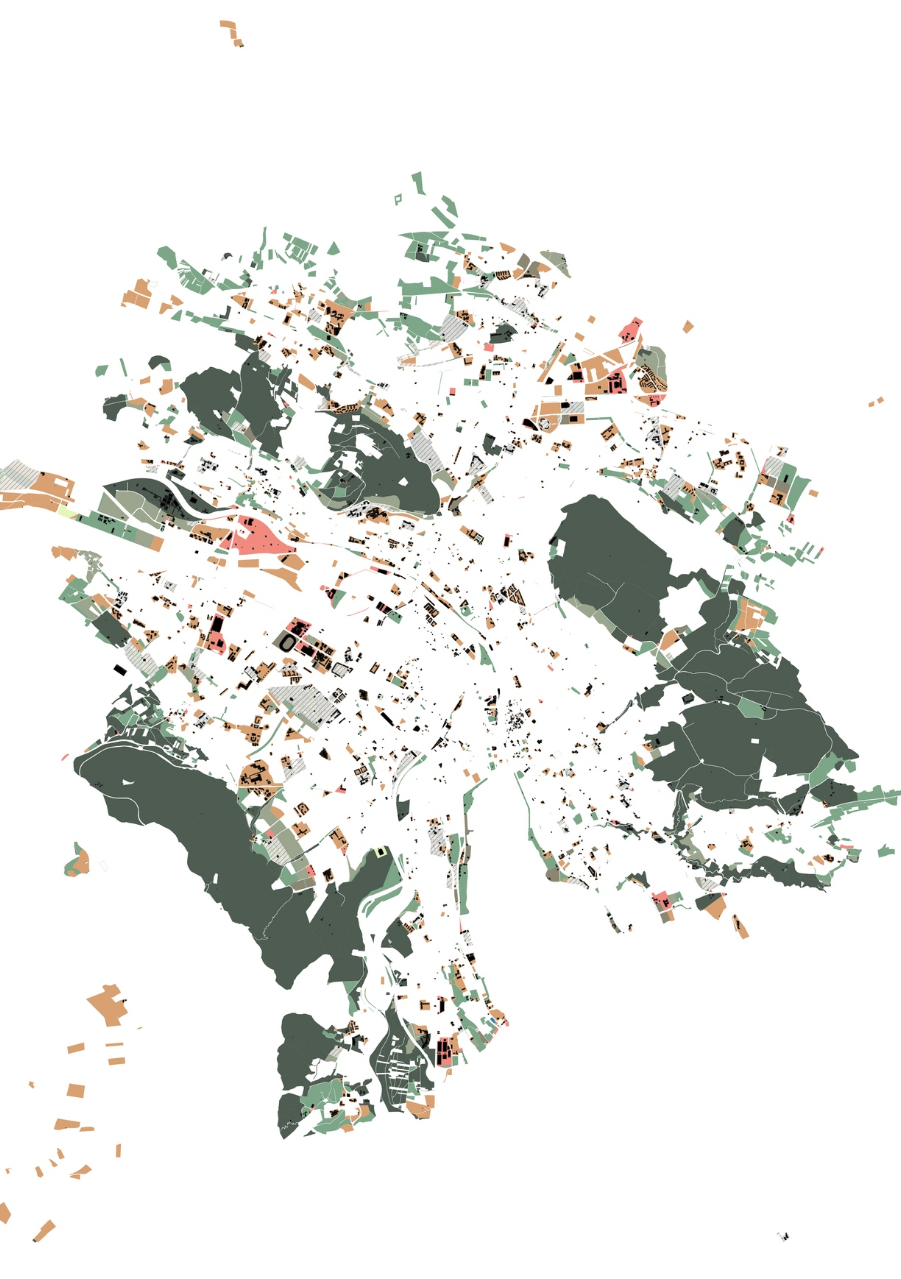

2) Regional production and distribution: 30 farms in Zürich, 1/10 of area for agricultural production, allotment-gardens, family gardens, school gardens; regional value chain

3) Procurement and catering: city led 450 restaurants act as rolemodels

4) Food waste and disposal: actions, campaigns, kitchen waste collection

5) Cooperation and monitoring: active People, farmers, network, assessment

In our talk with Yvonne Lötscher, she argues, that Zurich tries to act as a role model in their municipal restaurants. They observe that many people eat in a city institution such as a school, staff restaurant, daycare center, hospital, retirement or nursing center - there they can directly intervene. The 450 municipal restaurants provide about 7 million menus a year. They are planning to reduce their food waste until 2030 by <10 %, offer healthy menus by >50% added value and reduce their environment value by minus 30%. They are stating «Zurich has the best prerequisites for sustainable nutrition. New collaborations between consumers and producers are blossoming across the city, and associations and organizations are getting involved in the topic of nutrition. The diverse, multicultural restaurant sector creates new, enticingly sustainable offerings almost daily. In its own 450 establishments, the city of Zurich is making sustainability an integral part of culinary enjoyment.»(9)

They also suggest to reduce food losses in production and processing, make careful menu and purchasing planning, establish appropriate packaging and storage, offer sensible menu offerings and portion sizes and use their leftovers creatively. They advise the inhabitants of the city: «If there are several variants of a product or product group to choose from: Choose seasonal products from the region and buy environmentally and socially responsible products.» (10)

They are also co-operating with Grün Stadt Zürich, for example through the municipal farm Juchhof (link) In total there are almost 30 farms in the city of Zurich - around one tenth of the city's area is used for agriculture. Additionally, there are more than 5,000 traditional allotment gardens, over 80 school and student gardens, and various communal green spaces. With these spaces the city is trying indirectly to enable the population to experience the cultivation of agricultural products or to get involved in it themselves. (11) The productive facilities within Zurich’s fabric could have potential to offer a different vision of cultivation. But these urban farmers are facing difficulties, as they have to follow different rules than their larger, more productive counterparts.

On a national level, agricultural production is largely supported by subsidies. These are based on the size of the farm and not, for example, on the number of jobs a farm provides. The agricultural policy thus promotes the growth of farms and thus prevents other farm concepts. (12) According to current research, direct payments and other subsidies do not necessarily benefit sustainable measures. For example, the cost of biodiversity-damaging subsidies in agriculture is around 7.6 billion per year, while only 400 million per year is spent on biodiversity-enhancing subsidies. (13)

Those who wish to receive subsidies must provide «services of general economic interest» under Article 104 of the Federal Constitution: Namely, the maintenance of cultivated land, a contribution to the security of supply, the promotion of biodiversity, the preservation of a diverse landscape, and the application of environmentally and animal-friendly forms of production. (14)

However, shifting nutritional strategies could have an impact on how land is cultivated, tend and how the population is experiencing their connection to food. On a spatial and behavioral level these strategies does not seem to work yet, as it takes certain changes to shift ways and habits. With organizations as the «Ernährungsforum Zürich» that was also created within the new policies regarding sustainable nutrition, there seems to grow a vibrant environment to explore new ways of cultivation that are not necessarily crisis-driven, but stem from a deeper naturalness to the relationship with food. This structural change and the counter-movements are currently envisioning a direction for the future city. After all, these strategies could offer a potential to rethink existing structures and histories.